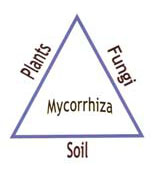

Mycorrhizal (pronounced my-core-RYE-zall) fungi have a mutualistic relationship with the plant roots that they colonize. The tiny strands of the fungi or mycelia extend far into the soil and become extensions of the plant’s root system. The mycelia increase the surface absorbing area of the roots by one to two orders of magnitude (10 to 100 times) thereby greatly increasing the plants ability to utilize soil nutrients and water absorption. Several miles of mycelium can be found in a thimble full of soil. According to Michael Miller, senior soil scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, “Basically, 90 percent of the world’s vascular plants belong to families that have symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi.”

Mycorrhizal (pronounced my-core-RYE-zall) fungi have a mutualistic relationship with the plant roots that they colonize. The tiny strands of the fungi or mycelia extend far into the soil and become extensions of the plant’s root system. The mycelia increase the surface absorbing area of the roots by one to two orders of magnitude (10 to 100 times) thereby greatly increasing the plants ability to utilize soil nutrients and water absorption. Several miles of mycelium can be found in a thimble full of soil. According to Michael Miller, senior soil scientist at the U.S. Department of Energy’s Argonne National Laboratory, “Basically, 90 percent of the world’s vascular plants belong to families that have symbiotic associations with mycorrhizal fungi.”

The mycorrhizal fungi increase nutrient uptake not only by increasing the surface absorbing root area but also by chemically dissolving phosphorus, iron, and other tightly bond soil nutrients. Due to the extensive network of mycelium, mycorrhizal plants also have a greater ability to take-up and store water than non-mycorrhizal plants decreasing drought stress.

Mycorrhizal fungi also improve soil structure by producing polysaccharides or organic glues that bind soils into aggregates and improve soil porosity. Improving the soil porosity and structure aerates the soil and promotes water movement, root growth, and root distribution.

Science has verified that when present, mycorrhizal fungi not only provide increased water, mineral, and nutrient uptake but also increase feeder root longevity by providing a biological deterrent to root infection by soil pathogens.

Most undisturbed soils already contain beneficial organisms including various types of mycorrhizal fungi. In native plant communities, certain mycorrhizas have coevolved with specific plant species. Undisturbed sites with native plant communities are likely to have functional mycorrhizas that will colonize the roots of newly planted native species. Conversely, non-native plants planted on these sites may or may not form associations with local mycorrhizal population.

Tillage, fertilization, removal of top soil, erosion, site preparation, road and home construction, fumigation, invasion of non-native species, and leaving soils bare are some of the activities that can reduce or eliminate beneficial soil fungi.

Routine nursery and greenhouse practices, such as fumigation and using high levels of water and nutrients, result in producing non-mycorrhizal plants. The high levels of fertilizer and water provided to non-mycorrhizal plants allow them to thrive in this artificial growing environment, however, they are ill prepared to survive in their eventual outdoor environment.

Mycorrhizal fungi, either naturally occurring or artificially introduced, are capable of colonizing the roots of numerous trees, plants, and food crops.

More and more companies have begun producing and selling mycorrhizal inoculants. Artificial mycorrhizal inoculation may benefit plants when

More and more companies have begun producing and selling mycorrhizal inoculants. Artificial mycorrhizal inoculation may benefit plants when

there are no natural mycorrhizas in the soil or the mycorrhizas are not appropriate for the species. Inoculation may be beneficial in highly impoverished soils (such as mine spoil sites) that cannot support natural fungi growth. New construction and home landscapes, where the topsoil

has been removed, may also be a prime candidate for artificial mycorrhizal inoculants.

Successful treatment with artificial inoculants cannot be guaranteed since (1) the existing soil may already contain native mycorrhizal fungi that will out-compete the introduced mycorrhizas or (2) the soil organic matter content may not be adequate. The presence of organic matter is known to enhance the development of mycorrhizae.

Commercially produced mycorrhizal inoculant fungi for plants, trees, and food crops are on the rise. These inoculants have the fungal spores “enhanced” with root stimulants, fertilizers, humic acids, water absorbent gels, and other ingredients that are intended to invigorate roots and promote plant growth.

The debate, however, continues over the validity of applying these artificial mycorrhizal inoculants to the soil. There is very little, unbiased scientific evidence to confirm that mycorrhizal inoculation of plants actually improves their growth and survivability compared to non-inoculated species. The available evidence is rather inconsistent.

Either commercially prepared inoculants are not very viable or that they are not viable by the time they reach the consumer. Any short-term positive effects on plant growth might be attributed to the fertilizer components and other ingredients that are often present in the commercially available mycorrhizal inoculants.

Let us recap some of the recently published scientific research that examines the validity of claims made by some commercially produced inoculants.

- Liquidambar styraciflua (sweetgum) inoculated with commercial products from Earth Roots, MycoApply endo, and VAM 80 had greater leaf area, dry mass, and growth rate relative to non-mycorrhizal sweetgum in a nursery environment. Two other commercial

products showed no relative growth enhancement compared to a non-inoculated, control sweetgum. (Effectiveness of Commercial Mycorrhizal Inoculants on the Growth of Liquidambar styraciflua in Plant Nursery Conditions. J. Environmental Horticulture (2005), 23(2):72-76. Corkidi, Lea, et al.) - Hardwood and pine forests in North Carolina and New Hampshire showed that active fungal biomass was 27% to 69% lower in the fertilized plots compared to the control plots. Active bacterial biomass was not greatly affected by nitrogen additions. Ectomycorrhizal fungi community diversity was lower in the nitrogen treated plot than in the control plot. (Chronic Nitrogen Enrichment Affects the Structure and Function of the Soil Microbial Community in Temperate Hardwood and Pine Forests. Forest Ecology and Management (2004) 196: 159-171; Frey, S.D. et al.)

- A methodology has been developed for preparation and use of vascular-arbuscularmycorrhiza for seed treatment in the form of a slurry application that show promising signs that indicate enhanced plant growth of economically important agricultural and horticultural crops in New Delhi. (Mycorrhiza and its Significance in Sustainable Forest Development. Orissa Review, India (2004). Mishra, B.B. et al.)

- Using established Quercus palustris (pin oak), Quercus phellos (willow oak), and Acer rubrum (red maple), scientists found no apparent measurable growth benefit to inoculation with a commercial mycorrhizal fungal product, unless it was combined with fertilizer.

(Mycorrhizal Fungal Inoculation of Established Street Trees. J. Arboric (2003) 29:107-110. Appleton, B., et al.) - In the oak savanna in Minnesota, increased nitrogen supply decreased the diversity and shifted the composition of ectomycorrhizal fungal communities. (Long-term Increase in Nitrogen Supply Alters Above and Below Ground Ectomycorrhizal Communities and Increases the Dominance of Russula spp. In a Temperate Oak Savanna. New Phytologist (2003) 160:239-253; Avis, P.G., McLauglin, D.J. et al.)

- In a study with Quercus phellos (willow oak), trees inoculated at the time of installation showed no survival or growth enhancement one year after the inoculation treatment. (Can Mycorrhizae Improve Tree Establishment in the Landscape? Proc. SNA Res. Conf. (200) 45:405-407; Calson, J., et al.)

- Established Quercus virginiana (live oak) showed a significant and rapid increase in fine root development six months after fertilizer, mycorrhizal inoculant, and fertilizer/mycorrhizal inoculant treatments. (Root Response of Mature Live Oaks in Coastal South Carolina to Root Zone Inoculations with Ectomycorrhizal Fungus Inoculants. J. Arboric (1997) 23:257-263; Marx, D.H., et al.)

The bottom line seems to be that artificial inoculation may have either a positive or neutral effect on plant growth and health. In any case, artificial inoculation has not been found to be injurious to the plants.

I’ll be trying mycorrhizal inoculants this spring when I do my annual attempt at propagation. It may take several seasons to determine the results but I will report them to the GMG.

Research indicates that organic soil amendments, particularly the addition of composted mulches, greatly enhance the mycorrhizal status of landscape plants without the addition of artificial mycorrhizal inoculants. Other research suggests that the jury is still out.

If you already have a healthy soil, you probably don’t need inoculants. Improvements in soil conditions may really be the most important factor in mycorrhizal development in the landscape. To encourage your own mycorrhizas:

- Avoid as much as possible soil disturbances such as annual tilling.

- Avoid the use of synthetic pesticides, especially fungicides.

- Avoid soil compaction.

- Where possible, avoid the removal organic material, like leaves, from the beds.

- Mulch with partially composted leaves and other organic material.

- Encourage birds and other beneficial wildlife to visit your garden.

- When planting native trees and shrubs, add some organic duff from the woodland near your home to the planting hole. This duff likely contains spores of locally occurring mycorrhizas.